Recently the open-access PLoS Biology published a really cool study in experimental evolution, in which a disease-causing bacterium was converted to something very like an important plant symbiont. The details of the process are particularly interesting, because the authors actually used natural selection to identify the evolutionary change that makes a pathogen into a mutualist.

Recently the open-access PLoS Biology published a really cool study in experimental evolution, in which a disease-causing bacterium was converted to something very like an important plant symbiont. The details of the process are particularly interesting, because the authors actually used natural selection to identify the evolutionary change that makes a pathogen into a mutualist.

Life as we know it needs nitrogen – it’s a key element in amino acids, which mean proteins, which mean structural and metabolic molecules in every living cell. Conveniently for life as we know it, Earth’s atmosphere is 78% nitrogen by weight. Inconveniently, that nitrogen is mostly in a biologically inactive form. Converting that inactive form to biologically useful ammonia is therefore extremely important. This process is nitrogen fixation, and it is best known as the reason for one of the most widespread mutualistic interactions, between bacteria capable of fixing nitrogen and select plant species that can host them.

Clover roots, with nodules visible (click through to the original for a nice, close view. Photo by oceandesetoile.

Clover roots, with nodules visible (click through to the original for a nice, close view. Photo by oceandesetoile.In this interaction, nitrogen-fixing bacteria infect the roots of a host plant. In response to the infection, the host roots form specialized structures called nodules, which provide the bacteria with sugars produced by the plant. The bacteria produce excess ammonia, which the plant takes up and puts to its own uses. The biggest group of host plants are probably the legumes, which include the clover pictured to the right, as well as beans – this nitrogen fixation relationship is the reason that beans are the best source of vegetarian protein, and why crop rotation schemes include beans or alfalfa to replenish nitrogen in the soil.

For the nitrogen-fixation mutualism to work, free-living bacteria must successfully infect newly forming roots in a host plant, and then induce them to form nodules. The chemical interactions between bacteria and host plant necessary for establishing the mutualism are pretty well understood, and in fact genes for many of the bacterial traits, including nitrogen-fixation and nodule-formation proteins thought to be necessary to make it work are conveniently packaged on a plasmid, a self-contained ring of DNA separate from the rest of the bacterial genome, which is easily transferred to other bacteria.

This is exactly what the new study’s authors did. They transplanted the symbiosis plasmid from the nitrogen-fixing bacteria Cupriavidus taiwanensis into Ralstonia solanacearum, a similar, but disease-causing, bacterium. With the plasmid, Ralstonia fixed nitrogen and produced the protein necessary to induce nodule formation – but host plant roots infected with the engineered Ralstonia didn’t form nodules. Clearly there was more to setting up the mutualism than the genes encoded on the plasmid.

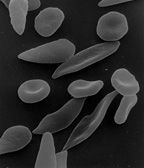

Wild-type colonies of Ralstonia (tagged with fluorescent green) are unable to enter root hairs (A), but colonies with inactivated hrcV genes are able to enter and form “infection threads,” like symbiotic bacteria (B). Detail of Marchetti et al. (2010), figure 2.

Wild-type colonies of Ralstonia (tagged with fluorescent green) are unable to enter root hairs (A), but colonies with inactivated hrcV genes are able to enter and form “infection threads,” like symbiotic bacteria (B). Detail of Marchetti et al. (2010), figure 2.This is where the authors turned to natural selection to do the work for them. They generated a genetically variable line of plasmid-carrying Ralstonia, and used this population to infect host plant roots. If any of the bacteria in the variable population bore a mutation (or mutations) necessary for establishing mutualism, they would be able to form nodules in the host roots where others couldn’t. And that is what happened: three strains out of the variable population successfully formed nodules. The authors then sequenced the entire genomes of these strains to find regions of DNA that differed from the ancestral, non-nodule-forming strain.

This procedure identified one particular region of the genome associated with virulence – the disease-causing ability to infect and damage a host – that was inactivated in the nodule-forming mutant strains. As seen in the figure I’ve excerpted above, plasmid-bearing Ralstonia with this mutation were able to form infection threads, an intermediate step to nodule-formation, where plasmid-bearing Ralstonia without the mutation could not. Clever use of experimental evolution helped to identify a critical step in the evolution from pathogenic bacterium to nitrogen-fixing mutualist.

References

Amadou, C., Pascal, G., Mangenot, S., Glew, M., Bontemps, C., Capela, D., Carrere, S., Cruveiller, S., Dossat, C., Lajus, A., Marchetti, M., Poinsot, V., Rouy, Z., Servin, B., Saad, M., Schenowitz, C., Barbe, V., Batut, J., Medigue, C., & Masson-Boivin, C. (2008). Genome sequence of the beta-rhizobium Cupriavidus taiwanensis and comparative genomics of rhizobia. Genome Research, 18 (9), 1472-83 DOI: 10.1101/gr.076448.108

Gitig, D. (2010). Evolving towards mutualism. PLoS Biology, 8 (1) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000279

Marchetti, M., Capela, D., Glew, M., Cruveiller, S., Chane-Woon-Ming, B., Gris, C., Timmers, T., Poinsot, V., Gilbert, L., Heeb, P., Médigue, C., Batut, J., & Masson-Boivin, C. (2010). Experimental evolution of a plant pathogen into a legume symbiont. PLoS Biology, 8 (1) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000280

![]() Many insects in the order Hemiptera – the “true” bugs – have evolved a way to hire their own protection by excreting sugary “honeydew.” Honeydew attracts ants, who tend honeydew-producing bugs like livestock, protecting them from predators and even disease. Honeydew is cheap to make because honeydew producers typically make a living sucking the sap of their host plants; they’re trading sugar and water, which they have in abundance, for safety.

Many insects in the order Hemiptera – the “true” bugs – have evolved a way to hire their own protection by excreting sugary “honeydew.” Honeydew attracts ants, who tend honeydew-producing bugs like livestock, protecting them from predators and even disease. Honeydew is cheap to make because honeydew producers typically make a living sucking the sap of their host plants; they’re trading sugar and water, which they have in abundance, for safety.