![]() Even in the twenty-first century, infectious diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, cholera, and AIDS remain widespread in much of the developing world, at tremendous cost to human life and economic productivity. Poorer nations lack the resources for more effective public health measures; but widespread infectious disease may slow or prevent the economic development that can provide those resources. A new paper in Proceedings of the Royal Society tries to sort out this chicken-and-egg problem, and finds that economic development is the fastest route out of the “poverty trap” [$a].

Even in the twenty-first century, infectious diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, cholera, and AIDS remain widespread in much of the developing world, at tremendous cost to human life and economic productivity. Poorer nations lack the resources for more effective public health measures; but widespread infectious disease may slow or prevent the economic development that can provide those resources. A new paper in Proceedings of the Royal Society tries to sort out this chicken-and-egg problem, and finds that economic development is the fastest route out of the “poverty trap” [$a].

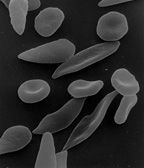

The paper’s authors, Bonds et al. start with a classic model of infectious disease, in which susceptible (healthy) members of a population have a chance of becoming infected whenever they encounter an infected person, and infected people have a chance to recover to susceptible condition if they survive the effects of the disease. The first probability is the rate of transmission from person to person; the second is the rate of recovery from disease caused by the infection.

Bonds et al. insert economics into this basic model by reasoning that the rate of recovery is a function of per-capita income – well-fed people are better able to fight off infection – and that income is a function of the proportion of the population that remains uninfected at any given time. This yields a mathematical version of the poverty trap I outlined above: high-income populations are easily able to fight off infection and remain near 100 percent susceptible, but highly infected societies are unable to increase their per-capita income to reduce their rate of infection. However, there is an internal equilibrium point – a level of income and infection from which a population could easily move in either direction, towards high income and low infection or high infection and low income.

The question then becomes how best to push a developing nation’s population toward that threshold condition – or how best to bring the threshold closer. Bonds et al. compare two options: reducing the rate of disease transmission, and boosting individual economic productivity. The former captures the effect of boosting public health – vaccination, better sewage treatment, food aid. The latter captures the effect of improving infrastructure or financial institutions – making the economy more developed. They found that the threshold condition is more sensitive to economic productivity. Even at low transmission rates, a society can be caught in the poverty trap if its productivity is low enough, but at high enough productivity levels, societies can avoid the trap created by even highly transmissible diseases.

This suggests that, although medical aid can help the acute problem of infectious disease, it’s investment in economic development that can ultimately solve it.

Reference

Bonds, M., Keenan, D., Rohani, P., & Sachs, J. (2009). Poverty trap formed by the ecology of infectious diseases Proc. R. Soc. B DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2009.1778