![]() Since her office is just down the hall from mine, I couldn’t very well write about Erica Bree Rosenblum’s latest scientific paper without talking to her about it in person. Rosenblum and her coauthor Luke Harmon weave together the stories of three lizard species’ evolutionary responses to the gypsum dunes of White Sands, New Mexico. As Rosenblum told me in our interview, the study both consummates work she began as a doctoral student and suggests new avenues of study at a striking and beautiful field site.

Since her office is just down the hall from mine, I couldn’t very well write about Erica Bree Rosenblum’s latest scientific paper without talking to her about it in person. Rosenblum and her coauthor Luke Harmon weave together the stories of three lizard species’ evolutionary responses to the gypsum dunes of White Sands, New Mexico. As Rosenblum told me in our interview, the study both consummates work she began as a doctoral student and suggests new avenues of study at a striking and beautiful field site.

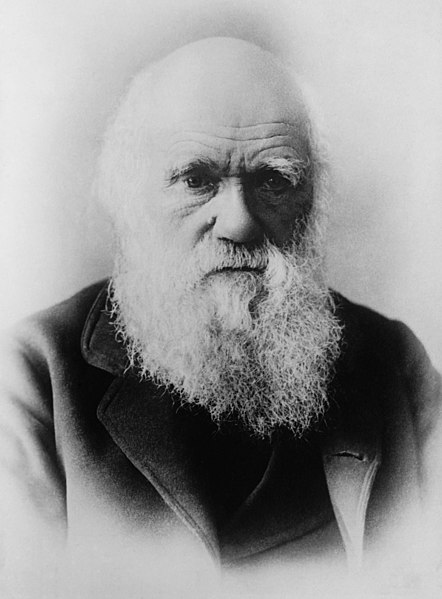

Erica Bree Rosenblum at White Sands, where she has studied lizards’ adaptation to the dramatic gypsum dunes since graduate school. Photo courtesy Erica Bree Rosenblum.

Erica Bree Rosenblum at White Sands, where she has studied lizards’ adaptation to the dramatic gypsum dunes since graduate school. Photo courtesy Erica Bree Rosenblum.(I’ve edited the transcribed interview for clarity and length, and paraphrased the questions I asked in person to minimize my interruptions. Rosenblum previewed, corrected, and approved the text of her answers and my questions as they appear below.)

Jeremy B. Yoder: Tell me about the new study and its context.

Erica Bree Rosenblum: Some of the things that are compelling about White Sands that motivated us to write the “Same Same but Different” [$a] are that there are a number of different species that colonized this recent formation. … At first blush, this system looks all “same same.” You look at the main trait that has allowed these animals to survive there, which is becoming light in color, and many diurnal animals at White Sands are white, unless they have some other strategy for avoiding predation. … So a lot of my work over the last several years has been focused on the “same same” aspect of convergent evolution and on the one trait that appears to be the key trait for colonizing, which is light color.

The motivation of this paper was that there is an enormous “but different” side to the story, because there are three lizard species there, and they exhibit some really compelling differences in their degree of adaptation and their progress toward speciation. And also if you start looking at other traits besides color, if you take a multidimensional perspective on adaptation, then there are a lot of really striking differences across species.

JBY: Body size and limb length?

EBR: Body size and limb length and also the genetic basis of color and how structured the populations are across the ecotone. [The transition zone between white sand dunes and dark soil – JBY] So the motivation for this study was to look at what are the essential factors for ecological speciation and then what are the promoting factors for ecological speciation and how might the three species differ.

JBY: How did you start studying the White Sands lizards in the first place?

EBR: I was co-advised in graduate school by two eminent evolutionary biologists who have opposite perspectives on how you find study systems. My first year in graduate school, my one advisor, Craig Moritz, said to pick the theory you are interested in first and then find the system that will let you address that theory. My other advisor, David Wake, said to pick something that you love aesthetically, and then learn more about that. So I had these competing influences, in that sense, when I was trying to form my dissertation project.

Rosenblum and her collaborator Luke Harmon pursue Sceloporus magister, a close evolutionary relative of one species that has colonized White Sands. Photo courtesy Erica Bree Rosenblum.

Rosenblum and her collaborator Luke Harmon pursue Sceloporus magister, a close evolutionary relative of one species that has colonized White Sands. Photo courtesy Erica Bree Rosenblum.I had just come back from a bunch of years abroad, and I knew I didn’t want to do research overseas. I also knew that I wanted to do my own thing and just “plug into” a system that had already been established. So I had an idea for wanting to do a study about ecotones—to study divergence with gene flow—in herps. [Lizards and snakes – JBY]

I had talked with different people and taken a map of the U.S. and circled every place that had really sharp transition zones that had to do with interesting problems in herpetology. So I had considered other field sites—in some of the lava flows in California that have strong transition zones, coastal-to-inland [transitions], these cool legless lizards in California—there’s a bunch of strong ecotonal transitions in western U.S. reptiles.

So I circled a bunch of places on the map and I was driving around catching animals and thinking about what I wanted to do. And when I got to White Sands, the Dave Wake part of me was drawn to it aesthetically. … It just seemed like such a striking example of adaptation with such clear possibilities. I knew I wanted to study something simple enough to wrap my head around, and White Sands has a striking, small, depauperate community, so you can actually study everything. And with a few exceptions, no one had done any biological research at White Sands since the forties, when the White Sands species were described.

JBY: What question would you like to have answered five years from now?

EBR: One of the big things I’d like to know is about the dimensionality of selection in the wild. We have a tendency to think about whatever trait seems most accessible to us, but when environments change, organisms are confronted with a lot of adaptive problems to solve at once.

… Number one is understanding the genetic architecture of adaptation and speciation. We know a lot about genotype to phenotype connections in natural populations, but we don’t know a lot about genotype-to-phenotype-to-speciation connections. I’m really interested in traits that might function as “magic traits,” that make speciation easier. I’m interested in whether [for White Sands lizards] color serves as a magic trait and can “high-tail” populations towards speciation.

The other thing I’m interested in is the genetic architecture of multidimensional adaptation. If you have lots of traits that are changing in a new environment, and it is happening very quickly over time, are the genes that underlie those adaptive traits all clustered in the genome? Is there a “signature” of multidimensional adaptation at the genetic level?

And then the third thing is about the predictability of evolution in general. I think it would be really fun to do a more systematic study of the entire fauna at White Sands and understand not just three lizard replicates but all the other species that are white, from invertebrates to mammals, to understand how predictable those adaptive changes are.

Different shades of Sceloporus undulatus, one of the three lizard species adapted to life at White Sands. Photo courtesy Simone Des Roches.

Different shades of Sceloporus undulatus, one of the three lizard species adapted to life at White Sands. Photo courtesy Simone Des Roches.JBY: What about ten years from now?

EBR: The challenge of working at White Sands is that it’s a compelling empirical system to test some classic population genetics ideas, but it’s very hard to develop general conclusions from one system with three replicates. It’s nice to have the three lizard replicates, but it’s still only one system in one place. I’ve tried to visit all the other gypsum sand dune systems in the world. There are others—in Texas, in Mexico … they have unique faunas in other ways, but none of them seem to have blanched species. So when you study natural systems, finding compelling evolutionary replicates can be difficult.

JBY: And when we go looking for study systems we often find the ones with the strongest signals first.

EBR: That’s right … Another example where we’re running into a problem is that … in two of the three species the gene that controls color is the same gene, but has different dominance patterns [PDF]. In one species the mutation that leads to white color is recessive and in the other it’s dominant. And there’s a longstanding debate from Haldane, of how dominance should influence adaptation, but it’s just an N of two. So we could get any pattern. We’re doing follow-up studies to see if the predictions would be upheld in terms of how dominance affects the rate at which adaptive alleles are fixed, and visibility to selection. But whichever way the story goes, it’s either the way you expect it or the way you don’t expect it, but it’s just two replicates. So that is one challenge of studying things in nature.

JBY: Let’s conclude with an outrageous, blog-oriented question: Is White Sands the new Galapagos Islands?

EBR: Yes. [Laughs]

JBY: That’s what I hoped you’d say.

EBR: There are things that are compelling about white sands not only for learning about evolution but also for teaching about evolution. One of the new grants I have is for integrating research and outreach there, because it’s such a compelling place to say, “this is how adaptation happens.” You can see it with your eye, and it’s exactly what you expect. We just finished helping build a new evolution museum at the visitor center at white sands. … So I think that it has cool potential for helping public education around evolution, and it’s not as expensive to go there as it is to go to the Galapagos!

References

Rosenblum, E., Rompler, H., Schoneberg, T., & Hoekstra, H. (2009). Molecular and functional basis of phenotypic convergence in white lizards at White Sands. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA, 107 (5), 2113-7 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0911042107

Rosenblum, E., & Harmon, L. (2010). “Same same but different”: Replicated ecological speciation at White Sands. Evolution DOI: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01190.x